“Focus” is a website from UBC Science that you can find here. A friend of our club and BCWF director, Gerry Paille, sent me this article and I think it’s worth re-posting. You can find the original article here.

Two UBC researchers are exploring the problem of dwindling salmon runs from opposite ends of the knowledge continuum—cutting edge genomics, and empirical evidence gathered over millennia by the Indigenous Peoples of the coast.

By Geoff Gilliard

At least 7,000 years ago, the First Nations of the densely populated North Pacific coast had already grown prosperous from the ocean’s bounty, particularly near salmon fisheries. The salmon runs were surging in 1791 when Chief Kayapulano welcomed to his territory Spanish Captain José Narváez, the first European explorer to sail the Salish Sea. Narváez anchored offshore not far from where the University of British Columbia’s Vancouver campus sits today, on the traditional territory of xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) people.

But Musqueam people were almost gone in 1791. The trade routes that fueled the pre-contact economy had carried an apocalypse of disease that preceded European mariners. Yet somehow, Musqueam held on to their teachings.

“In hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓, we refer to ourselves as xwəlməxw people, which means you belong to the Earth — the grammar conjoins you,” says Morgan Guerin, who is Chief Kayapulano’s sixth-great grandson and the senior marine planning specialist for Musqueam Indian Band. “Falling from that is a teaching that the environment is a relative. So, it’s not a case of ownership, but a case of responsibility. When we talk about fisheries management, of who we are as xwəlməxw people, stewardship always has to come first.”

Stewardship of Canada’s fisheries has not been a success story. In 1992, the Atlantic cod fishery collapsed. In British Columbia’s great salmon rivers today, Indigenous elders reported to fisheries scientist Dr. Andrea Reid that Pacific salmon catches are one-sixth of what they were 50 to 70 years ago.

Dr. Reid, who heads UBC’s new Centre for Indigenous Fisheries (CIF), recently interviewed 48 knowledge keepers from 18 First Nations across the three largest salmon rivers in B.C. — the Fraser, Skeena and Nass. Many Indigenous people living in the rivers’ watersheds identify themselves as “Salmon People” so important are the fish to their way of being.

With wild salmon stocks predicted to continue falling, could turning — or returning — to Indigenous knowledge provide part of the solution to rebuilding salmon runs? Or does attempting to meld the learnings of millennia with Western science make for an uneasy coexistence? Dr. Reid argues that there’s no need for either paradigm to take precedence over the other. She’s guided by a principle and a teaching called Etuaptmumk, Two-Eyed Seeing, as envisaged by Mi’kmaw Elder Dr. Albert Marshall.

Two-Eyed Seeing is about welcoming many knowledge systems to coexist without one needing to co-opt or fit within another.

“In order to bring people together at the same table we need to recognize that many knowledge systems are valid,” says Dr. Reid. “They are true reflections of people’s lived experiences and place-based knowledge in this world. We’re going to be able to better contend with the crises we face if we’re willing to bring together the knowledge that we can garner about the world through these different approaches and practices.”

When it comes to the crises confronting salmon, the threats are manifold. The leading contenders identified by the elders interviewed by Dr. Reid include aquaculture, climate change, contaminants, industrial development, and infectious diseases.

It is the infectious diseases stressor, and the salmon farms where the diseases incubate, that viral ecologist Dr. Gideon Mordecai is focusing on. Dr. Mordecai, a research associate at UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, is using genome sequencing to understand how viruses spread from salmon farms are contributing to the wild salmons’ dire state of affairs.

Salmon farming is contentious. A large body of peer reviewed research links open-net pen salmon farms to decreases in wild salmon returns. Environmental organizations and the majority of First Nations on the B.C. coast have been calling for the removal of open-net pen farms for decades — a transition supported by the majority of British Columbians. Meanwhile, supporters of the farms cite the estimated $1.5 billion they generate for the economy and the 4,700 jobs they create for coastal communities.

Open-net pen salmon farms are similar to feed lots for cattle. They hold a large number of fish in a small area — half a million or more — where disease can spread quickly despite the use of antibiotics. The net walls of the pens do nothing to stop the movement of parasites and viruses into the ocean where they infect out-migrating wild salmon smolts.

One of the more harmful diseases Dr. Mordecai found in wild Pacific salmon is the Piscine orthoreovirus (PRV). His research, done in collaboration with Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), Genome BC, and the Pacific Salmon Foundation, proved that PRV from salmon farms is transmitted to juvenile Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) migrating past the farms. Chinook are particularly susceptible to PRV. After they leave the rivers where they hatch, the juvenile fish spend their first winter at sea sheltering in sounds and inlets — the same places where salmon farms are typically located. Other salmon species swim directly out into the North Pacific Ocean.

“One way we can study infection is to use a genetic-based assay just like the PCR test people have been using during the COVID pandemic,” Dr. Mordecai says. “We use that same technology to screen fish for viruses. We screened hundreds of fish from salmon farms for an epidemiological study where we can determine, for example, that 70 per cent of the fish in the pens are infected with this virus. Similarly, we tested wild juvenile Chinook and found that the proportion of fish infected with this virus is higher the closer fish are to farms. That indicates that the farms might be important in the transmission of PRV.”

Knowing whether a virus is present answers the question of how many of the fish within a net-pen are infected over time, but genome sequencing takes things a step further. By reading the genetic sequence of a virus, researchers can see the similarities among viral strains between populations just as, during the COVID pandemic, scientist have been able to trace the paths of variants as they spread across continents.

“We can look at genomes collected in the Atlantic Ocean and compare those to the ones in B.C. and see that the virus we have here descended from those in the Atlantic,” Dr. Mordecai explains. “By collecting lots of samples, we can build up a picture of how these different viral variants move around the world. And because we have samples from different times and we know how quickly those mutations in a viral genome should accumulate, we can estimate the time of those movements as well.”

Analysis of the PRV genomes in B.C. waters indicate that the number of PRV infections in the region has increased by 100 times over the last 20 years, which aligns with the regional growth in farms. Ninety per cent of the salmon farms in B.C. are owned by three Norwegian companies. When the industry set up shop on the B.C. coast in the 1980s, Atlantic salmon eggs were imported from Europe to stock the farms because Atlantic salmon are easier to farm than Pacific salmon. PRV emerged in Norway in the late 1990s with disastrous results for the Norwegian salmon farming industry.

PRV is associated with a disease in Chinook salmon called “jaundice/anaemia” in which the blood cells of the hosts are infected by the virus. This leads to the blood cells bursting which causes damage in the liver and kidneys. In extreme cases the fish turns yellow. Atlantic salmon react differently than Chinooks to the virus. Rather than causing blood cells to rupture, PRV causes a more chronic disease in the heart of Atlantic salmon, an important point when considering the risk posed by this virus to wild Pacific salmon.

“The salmon farming industry argues that although PRV causes disease in Norway, we have a less virulent version here,” Dr. Mordecai says. “There is some truth that in Atlantic salmon, the lineage of the virus we have here doesn’t appear to be as virulent as other lineages, but that doesn’t predict what the severity of disease is in other species. We can’t make risk assessments based on Atlantic salmon when we’re interested in different species of salmon here in B.C.”

The Cohen Commission of Inquiry into the Decline of Sockeye Salmon in the Fraser River in 2012 identified DFO’s conflicting mandate “to regulate salmon farms for the conservation of wild salmon, and on the other hand to promote salmon farm development and products.” It’s a balancing act Justice Cohen called “unmanageable” and recommended that the promotion of salmon aquaculture be removed from DFO.

One way to improve the survival rates of wild salmon is to reduce their interactions with salmon farms, either by closing the farms or raising fish in tanks on land. Although there is increasing pressure to phase out open-net pen farms on Canada’s Pacific coast, the federal government recently renewed the remaining 79 farm licenses for two years. So far, the salmon farming industry in B.C. has been unwilling to transition to closed containment. DFO’s mandate remains unchanged.

Dr. Mordecai wants to make sure that Canada’s decision makers have the best evidence available.

“I’m much more enthusiastic about studying viruses, but if we don’t have a robust way to review all that science and make sure that it’s informing the decisions, then it’s pointless,” Dr. Mordecai says. “I want the research in front of MPs, the people in DFO and the fisheries minister.”

In May 2022 he testified before the federal Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans, where he shared his research, and his concern that the leadership at DFO wasn’t getting the complete picture when reviewing the scientific evidence.

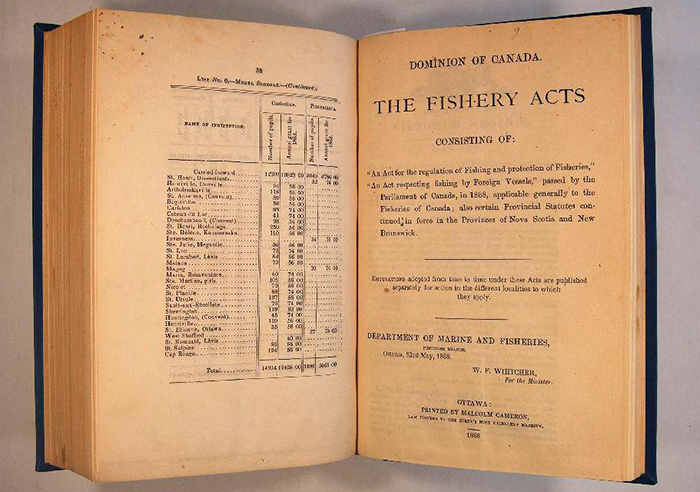

One year after Confederation, Canada introduced the Fisheries Act, which restricted Indigenous Peoples to managing their fisheries in a piecemeal fashion and criminalized traditional fishing practices. For all practical purposes it also barred them from participating in commercial salmon fishing. Early on, the Act allowed for participation in fishing for food. Then it allowed fisheries for social and ceremonial purposes. Over time, it’s allowed economic dimensions too, but curbed within the notion of a moderate livelihood.

Dr. Reid is a member of the Nisga’a Nation, whose traditional territory is the Nass River Valley in northern B.C. The Nisga’a hold the province’s first modern-day treaty, signed 22 years ago. Within that treaty, an entire chapter guarantees Nisga’a access to a portion of returning Nass River salmon. It also ensures the Nisga’a Fisheries and Wildlife Department, in operation since the 1990s, holds sovereignty over how its fisheries are managed.

“That’s a tall order for a lot of Nations,” Dr. Reid says. “It’s a very hard thing to achieve because those that hold power across fisheries management systems in Canada have been holding on to it tightly since colonization.”

In its first year of operation, Reid and her CIF colleagues have met with over 40 First Nations in B.C. that want to partner with the centre to think strategically about fisheries management. Musqueam and the five other First Nations in Metro Vancouver invited the CIF to help create a cultural health index that reflects Coast Salish knowledge and values through the First Nations Fisheries Legacy Fund. CIF graduate students Kasey Stirling and Kate Mussett are working with the Nations to identify values and indicators within Metro Vancouver watersheds as a first step to monitor the ecosystem in ways that reflect both its biological and cultural health.

“Our ambitions are to deliver science that is with and for community partners that responds to their needs and interests,” says Dr. Reid. “We’ve been putting in the work to understand what those are and begin to build partnerships that are truly equitable, and finding majority Indigenous students to be the leaders on the ground. It’s really important to me and to everyone in the centre that this is not just confined within the university setting.”

“I’ve got to wonder how much has been lost because I know how much we’ve retained — especially through residential schools,” says Guerin, the marine planning specialist for Musqueam and president of the First Nations Fisheries Legacy Fund.

Through plagues and systemic suppression, Musqueam who had learned knowledge from past generations looked for others who would listen and retain the knowledge and pass it on.

“Traditional ecological knowledge is a science system with tremendous rigour, because the delivery system is real oral history,” Guerin explains. “Growing up with our old people, man, their heads were wrapping a million things together when they were talking. This person just put 17 concepts together, some scientific, some theoretical. Oral history includes a true history which cannot be changed and a context that goes with it so you understand what that means.”

What might appear to be hearsay actually has a careful collection of cultural anchors and citations embedded in it, derived over many years.

“The story is considered a contextual component of the oral history, but not the actual true oral history. If I just go around telling stories but I leave out the first part because that wasn’t a part I liked, have I transferred that? No. Now it’s become a story rather than a piece of the history. It takes many years, many years to get to the point where someone is trusted to transfer our oral history.”

Guerin believes that a precursor to any negotiation with government requires they educate themselves in local Indigenous Peoples’ Ways of Knowing in order to understand First Nations’ positions.

“There’s a tremendous amount of tangibles and intangibles that come together when we try to present our oral history to a modern Western colonial government, when we’re talking about responsibilities,” he says.

“Where Canada recognizes our right to go out and access salmon, they’re still missing the defining characteristic of the responsibility to steward it at the same time, because there’s still that very colonial mindset. The ability to exercise that responsibility is still being taken away from us today.”

“My father came out of residential school and I watched him, in the best way possible, be a role model to myself and many others on how to keep the conversation on track. Because you know that transition isn’t going to happen today or in 100 years,” says Guerin. “What it requires is probably about two more generations of my people to maintain that resilience.”